If you have been infected with COVID-19 or have been in close contact with someone that has tested positive for the virus, it is likely that a contact tracer has been in contact with you.

Per the CDC, COVID-19 cases in the United States have surpassed 8.2 million and over 220,000 deaths as of Oct. 21. The data also shows that daily cases in the country have climbed back over the 60,000 mark on Oct. 20— the first time cases have reached that number since Aug. 7.

Because the cases continue to stagger upward, the demand for contact tracers is as high as it has ever been since the pandemic first started.

Jack Ritter is a contact tracer that completed his two-week training program earlier this month, and is now investigating COVID-19 cases for Maximus, a call center working with the Indiana State Department of Health.

Just in the spring, Ritter graduated from Indiana University with a degree in audio engineering and sound production. While waiting for the right opportunity to kickstart a career in his desired field, Ritter works on contact tracing from his Bloomington apartment.

He said it was a surprise to him how quickly Maximus moved him along in the hiring process.

“I reached out, and they didn’t even interview me,” Ritter said. “They’re just going through and hiring pretty much everybody at this point because there’s such a huge need for contact tracers. They just recently hired a batch of 125 new trainees at once I was training with.”

While waiting for an effective vaccine to distribute to the public for COVID-19, Indiana has invested $43 million into a contact tracing program the state launched back in April.

In this video, Ritter explains the step-by-step process of what happens during a call when someone has tested positive or has been in close contact with someone who tested positive for COVID-19.

“Essentially, contact tracing is the last line of defense in COVID. So, the first line would be things like social distancing, wearing masks, limiting interactions with others. Those are the kind of basic things we all need to be doing in order to prevent ourselves from getting coronavirus, infections, or if we do have it, prevent it from spreading to others,” Dr. Dan Guiles said. “Contact tracing happens after someone has been infected and potentially has spread the disease to other people.”

If a person in Indiana tests positive for COVID-19 or has been in close contact with an individual that tested positive, that person is likely to receive a text message from the ISDH that looks like this. (Fairbanks School of Public Health at IUPUI)

Guiles was initially hired by the IU Center of Global Health to work in Kenya, but because of the pandemic, his departure has been delayed. While awaiting for the global outbreak of COVID-19 to minimize, Guiles is working with a team for Indiana University composed of his role as a physician, two program managers, and two other leader individuals for contact tracing. His team of five meets daily to discuss the contact tracing challenges across all Indiana University campuses.

“Contact tracing really is effective and important, but we rely on the individuals to provide accurate information and to follow our recommendations,” Guiles said. “We’ve designed a pretty robust system for contact tracing.”

That system includes three main metrics that Indiana University health officials are reviewing to evaluate the effectiveness of their contact tracing efforts. They are:

- The percentage of individuals reached that have tested positive at Indiana University testing sites. This number is at 99 percent.

- Contact tracing efficiency, which is calculated by how quickly Indiana University contact tracers are reaching out to these individuals. This number is approximately 9 hours from the time the university gets the positive test result to the time the interview is completed by the contact tracer with the individual that has tested positive.

- The turnaround time that a lab test is resulted, to the time elapsed once the interview is completed. The current average is approximately 2.8 days.

In this video, Guiles explains the system Indiana University health officials and contact tracers use for contact tracing, along with the three main metrics the school monitors to evaluate the effectiveness of COVID-19 contact tracing efforts.

Additionally, the university has conducted over 5,400 contact tracing interviews since the semester started in August.

When asked about the state’s contact tracing force compared to the university’s efforts, Guiles provided a reason for why IU is not also using Maximus.

“Their response times are pretty slow, usually,” Guiles said. “They don’t have the knowledge of the university setting that they would need necessarily to do a really comprehensive job.”

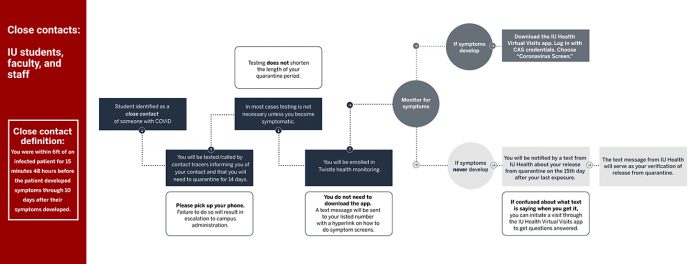

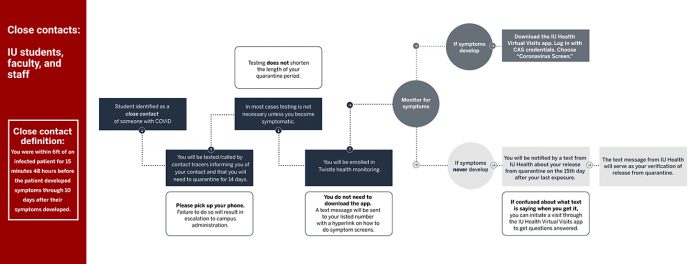

This chart explains how Indiana University deals with a person that has been in close contact with a person that tested positive for COVID-19. (IU Center for Global Health)

Contact tracing was not created specifically for COVID-19. According to Guiles, contact tracing has been a part of public health for quite some time.

“It’s been used a lot for other clinical diseases such as tuberculosis in particular, and used a lot in the ebola outbreaks in Africa. It’s a very established way to handle epidemics and pandemics,” Guiles said. “As far as doing it at Indiana University, this is a new thing for Indiana University that we’ve done.”

The Indiana University Fairbanks School of Public Health at IUPUI is still looking to hire up to 200 additional COVID-19 contact tracers through the end of the year as cases in Indianapolis (Marion Co.) have reached nearly 170 daily cases on average. To learn more about applying to become a contact tracer, you can send an email to covidct@iupui.edu.