“The Last Appeal” is a series uncovering the inadequate jail conditions and lack of health resources for those incarcerated at the Monroe County jail, despite efforts by law enforcement officers, and how this is not the only county jail in the country struggling with these complex issues.

In a letter to Monroe County Jail officials in late 2007, formerly incarcerated Trevor Richardson wrote: “I have been in jail here for 129 days and have been consistently subject to inhumane, unsanitary, and harsh living conditions.”

Richardson’s letter and the class action lawsuit he engendered is just one of many voices from all sides of the penitentiary system calling for greater resources to dramatically improve conditions in local jails around the United States.

Unsanitary and crowded conditions

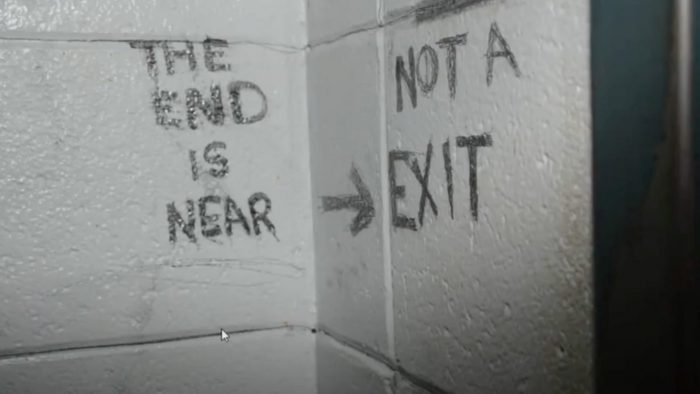

In 2007, Richardson described being forced to sleep on the floor of a small gymnasium with several others in the facility, where there was no bathroom access. The jail had only two showers and limited toilets for over 200 incarcerated people, he said. There were limited, if any, recreational opportunities, meals that were intended to be hot were served cold, and fights would break out over bed space, Richardson said.

The situation has only worsened since Richardson wrote his letter fifteen years ago. A 2020 Monroe County Criminal Justice and Incarceration Study noted that the jail has inadequate bed space, lacks mental health and medical facilities, and has limited space for segregated populations or those with special accommodations. The jail has outdated plumbing, lacks sanitation, and those in the facility have to navigate the multiple levels of the building

Limited facilities are just one of many problems. The study determined the facility has “exceeded its functional operating capacity.” While the current jail was built with a total capacity of 287 beds, the functional bed capacity is 80% of a jail’s total bed capacity, according to industry standards mentioned in the study. This would make Monroe County Jail’s functional capacity to be 230 beds.

The incarcerated population in 2019 ranged from 239 to 301 people monthly (thus above the jail’s capacity), according to another study, a 2021 Criminal Justice Report by Inclusivity Strategic Consulting. The study was one of the two reports commissioned by Monroe County to assess jail conditions.

And there is the exigent issue of the smell. An incarcerated person who has been in and out of the jail about five times said the smell of sewage permeates the jail.

“There’s no really was no air circulation…Half the time the toilet wouldn’t work. So you just gotta sit there by the toilet, ain’t gonna flush, just in somebody’s shit,” he said.

Monroe County’s current sheriff, Ruben Marté said what he cannot easily communicate to outsiders is the intense smell of the facility.

“You have to understand from our point of view, from our lens, now that you see this, quite frankly, it’s just not acceptable,” Marté said at a jail committee meeting. “No one should live in this type of condition. No one. And [another aspect I cannot even] bring, the smell or the sound.”

Marté’s administration has made substantial progress on cleaning up the jail since he took office last fall. Hallways and cell blocks have a fresh coat of paint, and the floors have been scrubbed clean. The outdoor recreation area has a newly painted mural on the walls. To create a calming environment to house those with mental health issues, a new wing has been painted blue.

For the jail staff, this was a necessary start, even if it doesn’t solve the facility’s core issues.

“It’s something that I think that all of us deserve. We all expect a clean environment to work in, a safe environment to work in. And I think [painting and cleaning the facility] kind of goes with it,” said an Officer working in the jail, who wishes to remain anonymous.

Nevertheless, the 2020 incarceration study made one thing clear: the facility has exceeded its structural and functional life cycle. The jail is “failing and cannot ensure consistent and sustainable provision of Constitutional Rights of incarcerated persons.”

An incarcerated person who has been in and out of the jail about five times said the smell of sewage permeates the jail.

Legal and constitutional issues

Richardson sued former Monroe County Sheriff Jim Kennedy and county commissioners over the jail conditions in 2008. This was part of a class action lawsuit that alleged that Monroe County’s Jail had “unconstitutional and unlawful conditions.” Richardson was represented by Ken Falk, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Indiana, who filed the lawsuit on February 1, 2008.

The ACLU lawsuit is subject to a private settlement agreement and is scheduled to end in January 2024. Falk said he has considered filing a new lawsuit next year or extending the current settlement agreement, but he hopes it does not come to that.

Fifteen years after he helped Richardson file his case, Falk was back in Bloomington in 2023 to speak to current county officials at a Monroe County Community Justice Response Committee (CJRC) meeting on the same issue.

“You guys are desperately wanting to do the right thing and treat people well, but it has hindered your ability to solve this problem,” Falk said. “And there is a very basic solution, which is, you have to build a new jail.

Tensions moving forward

The cost of building a new jail was estimated to be between $22 to $56 million dollars, according to calculations in the 2020 Incarceration Study. This estimate has not been addressed in detail in committee meetings.

The committee meeting, where Falk spoke recently, has been in session for more than two and a half years deliberating jail conditions and ways to move forward.

Meetings can be tense with disagreements and arguments between County commissioners, other county officials, and the public who can attend the committee’s open meetings.

Meetings can be tense with disagreements and arguments between County commissioners, other county officials, and the public who can attend the committee’s open meetings.

The issues related to building a new jail are also complex, from land availability and areas where the facility can be relocated, to the Bloomington community’s disdain for how the commissioners have handled the situation.

“[The community and the committee] haven’t heard from us yet about what our intentions are, what we think, and that can fuel confusion or a sense that we’re working somewhere behind the scenes. We’re not,” said Julie Thomas, a Monroe County Commissioner. “Sometimes, for people on the committee, it can be frustrating because we’re not actually moving forward yet. It’s okay. We don’t have to move forward today. We don’t have to move forward next week, but we are going to move forward.”

Marté’s administration has made substantial progress on cleaning up the jail since he took office last fall.

The current Sheriff, Ruben Marté however feels a new jail is necessary and time is running out on the current facility.

“I have no problem reaching out to cross the aisle and working with you [the county commissioners] in any capacity that I can,” Ruben Marté said. “But right now, the present time, right now, that jail is deteriorating at a fast rate. We gotta find a location and we gotta start [taking action now].”

The fresh paint and clean-up of the jail is not a sustainable solution, Marté stated to the commissioners at a committee meeting. He said time is running out for this facility.

When Trevor Richardson wrote a letter to jail officials in 2007, he wanted corrective action to occur. Richardson said in the 2007 letter, “I would like to see conditions improve, however, it seems like they are getting worse.”

Almost 16 years later, Sheriff Marté echoes Richardson’s plea.

“It’s getting tremendously worse…I don’t think you fully understand the ramifications of what I’m saying to you. It’s going to be very serious,” Marté said. “Please act back now. Start the process. Don’t sacrifice good for perfect, don’t do that.”

The lack of health care and mental health resources are at the core of high recidivism rates at the Monroe County Jail. In the next story, incarceration-focused non-profits and experts question whether a new jail will fix these complex issues.

“The Last Appeal” Part 2: Lack of health care at the core of high recidivism rates at Monroe County jail: Is building a new jail the solution?