“The Last Appeal” is a series uncovering the inadequate jail conditions and lack of health resources for those incarcerated at the Monroe County jail, despite efforts by law enforcement officers, and how this is not the only county jail in the country struggling with these complex issues.

Overcrowding, outdated facilities, and high recidivism rates are just a few of the many reasons that lead to county jails in the state of Indiana and nationwide being in constant states of distress and neglect.

Further state policies have contributed to increases in county jail populations and the facilities’ disintegration. To reduce state prison populations, Indiana enacted new laws in 2015 requiring those with low-level felonies to serve their sentences under county supervision, often in county jails, rather than state prisons. County jails were already facing overcrowding and unsanitary conditions prior to these state policy actions.

Widespread jail construction is the result.

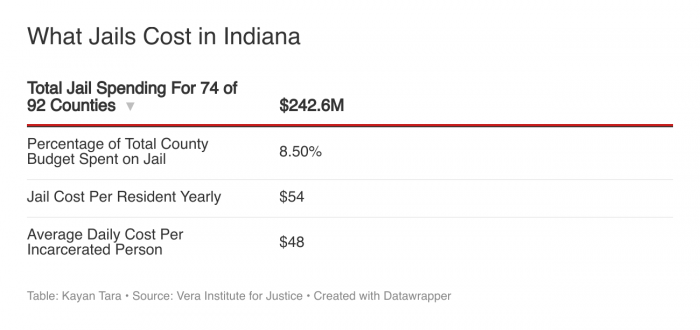

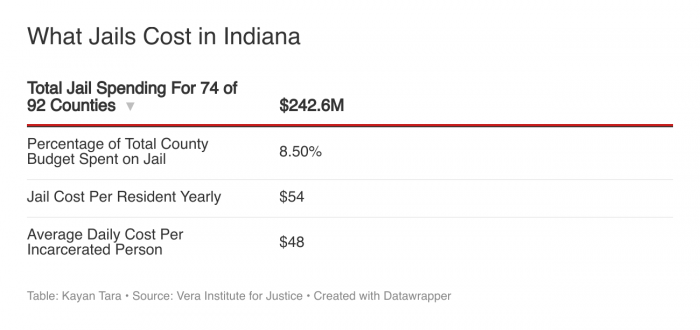

More than a third of Indiana’s 92 counties were actively building new jails, as of 2019. Indiana is among the top five states with the most pronounced jail growth, with the state spending over $242.6 million dollars a year on all jail-related costs.

From lawsuits against county jails to the unconstitutional treatment of incarcerated people, county jails around the nation struggle to provide lasting rehabilitation to those incarcerated. Experts and advocacy groups have differing opinions on potential solutions to these pressing issues.

Indiana is among the top five states with the most pronounced jail growth.

Financial Burden of Indiana’s County Jails

Larger jails can make profits off of housing incarcerated people from smaller counties, according to data from the Vera Institute of Justice, a nonprofit organization focused on research and policy organization around the justice system.

But counties that build bigger jails find that often their plans backfire. The profit generated from housing people from smaller counties and rural areas often does not cover the costs of a larger facility with more staff and significantly higher expenses.

This leads to county jails across the United States with deteriorating facilities due to a lack of funding. And plans to build new facilities are drawn out in practice, leaving current facilities with outdated and worn-out infrastructure.

More than half of the nation’s country jails are over 40 years old, with many in need of significant repairs and renovations, according to a report by the Vera Institute of Justice.

The Vera Institute data illuminates how jail costs put an outsize burden on Indiana’s smaller cities and rural communities. The average cost per Hoosier in jail was $54 per year, as of 2019. In comparison, rural counties in Indiana spent more on jails per overall resident at $72 per resident, and $116 per resident ages 15 to 64, as of 2019.

Miriam Northcutt Bohmert is an associate professor of criminal justice at Indiana University. The core of the issue is often left unaddressed when bigger facilities are built, she noted.

“If you build it, they will come…Bigger [facilities are] not better. I’m one of the people who would say [officials should] be very careful about building a new facility with more beds,” said Miriam Northcutt Bohmert, an associate professor of criminal justice at Indiana University. “If there are more beds all of a sudden, then are we gonna work as hard to keep people out?”

As conversations around building new facilities take years, issues in old jails are exacerbated by overcrowding. As the number of incarcerated people in county jails has increased, many facilities have been forced to double and even triple up people in small cells designed for one or two people.

Facilities not designed to withstand these conditions then become unsafe and unsanitary for incarcerated people. This can lead to a higher risk of tension, illness, and injury for both incarcerated people and staff members in the facility.

In early 2019, Hancock County, Indiana, planned to build a new jail with 440 beds, a vast increase from their previous facility’s 157-bed capacity. The costs to build a new, bigger facility were estimated to be as high as $9.3 million dollars annually. A new facility had a big opening in 2022 with a crowd of over 200 residents watching the Sheriff cut a bright-green ribbon.

In Vigo County, Indiana, officials raised income tax to construct a new jail. Officials estimated an increase in operating costs from around $5 million to nearly $7 million yearly. The county still owed nearly $1 million to pay off the bond for their current facility as of 2019.

While Indiana is among the top five states with the most jail growth, other states with jail expansion projects suggest this might not solve the problem.

The Financial Burden of Disintegration and Rebuilding

Gwinnett County, Georgia, completed a $78 million dollar jail expansion in 2006, with an addition of 1,440 beds to combat overcrowding. Four years later, incarcerated people were triple bunking in units built for only two people, as six housing units with 360 beds remained empty. The county was unable to finance the staff to operate these additional units.

Northcutt Bohmert notes jails are often used as a funding stream. Even if specific counties might not require a high bed capacity, by building a larger jail they can profit off of other counties sending incarcerated people to their facilities.

While Indiana spent at least $242 million in 74 of the state’s 92 local jails as of 2019, the figure does not capture the full cost of local incarceration in the state due to the lack of available data.

Unlike federal and state prisons, county jails operate on limited, local budgets. The cost of maintaining and upgrading aging infrastructure is up to individual counties and can be costly.

“When we run up against that capacity, we can pay other local jails that are nearby. We pay them to house our people. And that obviously costs more than if we could house them locally. But those jails then make a profit. So some jails are being used, even when they’re state-run or county-run, they’re not privatized jails. They’re still government-run, but their purpose really is to turn a profit,” said Northcutt Bohmert.

The solution is far from simple. Counties that do not fix issues of unsanitary and unconstitutional conditions face lawsuits, which force them to act or face greater financial and legal consequences.

Mounting Lawsuits for County Jails

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in lawsuits against county jails in the United States, for issues ranging from inhumane living conditions to inadequate medical care and overcrowding. These lawsuits have been brought forth by former or current people in jail, their families, or advocacy groups against incarceration.

County jails in Indiana have their own history of lawsuits.

Vigo County faced three consecutive rounds of civil rights litigation due to overcrowding. While the county doubled the jail’s capacity after a 2001 lawsuit, the facility exceeded the cap in the years following.

The most recent lawsuit in 2016 again cited overcrowding and deteriorating jail conditions as a violation of the Eighth and fourteenth amendments. Ultimately, Vigo County commissioners approved a sales tax to pay for a new, larger jail effective January 2018, with 527 beds, nearly double the capacity of the current facility.

The current jail in Delaware County was constructed as a result of a 1978 lawsuit over unconstitutional conditions. But when it opened, it was quickly deemed too small and outdated and soon became overcrowded.

The Indiana Department of Correction (IDOC) notified Delaware County in 2016 that its jail was noncompliant with state jail standards since it was understaffed and overcrowded. In 2018, more than two dozen handwritten lawsuits were filed by incarcerated people in the facility, alleging overcrowding and unsafe, inhumane living conditions.

In 2018, county officials agreed to buy and repurpose a former school for a new 500-bed jail at a cost of between $37 million and $45 million.

“[The United States has] a super, super high incarceration rate compared to any other place on the globe, and so our citizens are asked to pay a lot of money for a lot of people to go to jail and prison, and they don’t want to do it. And so then [officials] cut corners [to save costs]…People have health emergencies, they’re not cared for, and they die. So there are just so many problems and there’s not really political will or motivation in most communities or resources to fix that,” said Northcutt Bohmert.

The cases in Indiana counties are not isolated incidents, and similar lawsuits have been filed against county jails around the country. Lawsuits also attract attention, which comes with many calling for systemic changes to the criminal justice system and the ways in which incarcerated people are treated.

Inhumane Treatment of Incarcerated People

Earlier this year, a Monroe County correctional officer was fired after a violent “brawl” with an incarcerated person. In the Jackson County jail, an incarcerated person died after being neglected by jail staff.

“[Jails and prisons are] just not the best environment for people to be. You don’t want to send someone into a facility and have them come out even worse than when they went in,” said Northcutt Bohmert. “It’s not good for them. It’s not good for the community. It’s not even from a financial standpoint. It’s not good for taxpayers if people are just gonna commit more crimes, have more medical needs, have more substance use issue.”

Statistics have shown that county jails nationwide are filled with people from low socioeconomic backgrounds and those experiencing mental health crises and substance use disorders.

Not only do these circumstances lead to overcrowded and unconstitutional living conditions in county jails, they directly result in record-high deaths of and violence against incarcerated people.

More than half of all jail deaths occur within a month of an individual being booked into jail. Nationwide, there were 1,120 deaths a year reported in 2018. The number of deaths in local jails due to drug or alcohol intoxication has more than quadrupled between 2000, at 37 a year, and 2018, at 178 a year.

“How do we expect people to live when they can’t afford housing or childcare or transportation? I mean, these are basic human needs that people don’t have. And a lot of incarcerated people are committing crimes because they don’t have enough resources,” said Donyel Byrd, a social worker in Bloomington.

In some cases, those incarcerated are six times more likely to experience serious psychological distress than people with no involvement in the criminal justice system. A 2020 study found that prisons and jails are “exposure points” for extreme violence that undermine rehabilitation, reentry, and the mental and physical health of individuals.

“Justice isn’t blind, and I can tell you once you’re caught up in the system, people don’t understand how hard it is to get out,” said Byrd. “When people [say jail] is a way to get people help, I’m like, ‘you have just sentenced them to a lifetime of barriers that most of us who are walking around free, who haven’t been incarcerated, couldn’t get out of.’ People are set up in impossible situations.”

The reality is complex, Byrd notes, and the criminal justice system is a hard cycle to get out of for those incarcerated.

A More Fundamental Question

While issues in county jails have long been a concern, recent reports and increased attention are putting pressure on county officials to address the challenges faced by incarcerated people in Monroe County.

“There’s no data that suggests higher incarceration rates make us safer. There’s so much evidence on harm reduction. And how do we expect people to live when they can’t afford housing or childcare or transportation? I mean, these are basic human needs that people don’t have,” Byrd said.

Advocacy groups have been pushing for reforms to improve the conditions in county facilities, including reducing overcrowding, providing adequate medical care, and increasing access to mental health services.

However, a more fundamental question often remains unasked and therefore not addressed.

In the US, 505 per 100,000 people are in jail. This is the sixth highest rate in the world. The US has 4.2 percent of the world’s population yet 20 percent of the world’s prisoners. Overcrowded jails reflect deeper problems in society.

“It’s important for us when our citizens go [into jail or prison] that we believe…whatever’s happening there still enables them to be good citizens and enables our democracy to stay strong,” said Northcutt Bohmert. “And it can’t be strong if we’re sending only certain people to those places and hiding them away, and making it worse for them and their communities and their families…that’s how society has been weakened. It’s not weekend because [all incarcerated people are] a safety threat.”

“The Last Appeal” is a series uncovering the inadequate jail conditions and lack of health resources for those incarcerated at the Monroe County jail, despite efforts by law enforcement officers, and how this is not the only county jail in the country struggling with these complex issues.