Thieneman Brothers Tackle the Challenges and Opportunities of NIL in College Football

By Allie Davis, Kadie O’Bannon, Gracie Paul

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. (Nov. 5, 2024) —

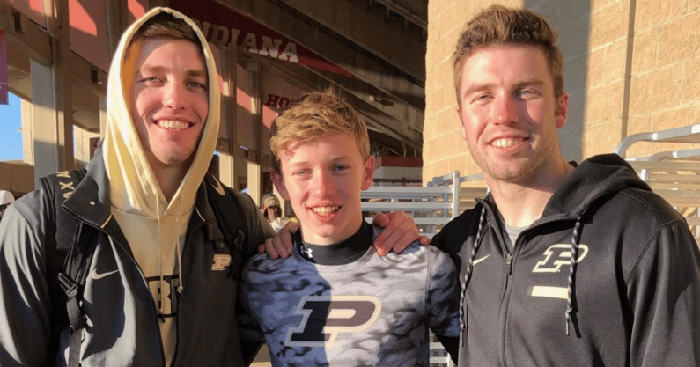

Brothers Jake and Dillon Thieneman have been playing football for as long as they can remember. Little did they know that their passion for the game could turn into a revenue-earning career.

This revenue is known as something called NIL, or name, image and likeness.

Jake Thieneman is a former Purdue safety and 2018 graduate, while Dillon Thieneman is a current sophomore safety at Purdue. Jake Thieneman began his journey at Purdue as a walk-on in 2014, and by his fifth year, he had climbed his way to team captain and starter. Dillon Thieneman had a different experience; he graduated high school after his first trimester senior year to begin playing for Purdue in the spring semester. Dillon Thieneman quickly earned his starting position as a true freshman safety. During his first year, Dillon Thieneman was named Third-team All-American, Big Ten Freshman of the Year, and Second-team All-Big Ten.

NIL has been a recurring topic over the past decade. One pivotal event reshaped the discussion: the House v. NCAA settlement. Filed in 2020, this lawsuit was brought by former Arizona State swimmer Grant House and former TCU and Oregon basketball player Sedona Prince, who sued the NCAA for its past ban on athletes getting compensated for their name, image and likeness before 2021. They argued that the ban violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act by restricting athletes’ ability to receive fair earnings. As of May 2024, the NCAA is facing a $2.78 billion settlement, potentially allowing Division I athletes to receive back pay for missed NIL opportunities and aiming to establish a more equitable system for current and future athletes.

The NCAA is expected to grant $1.2 billion, with Power Five Conference schools covering 24% of future withheld revenues. Over the next decade, money will be distributed to athletes who played between 2016 and 2021. If approved, universities would begin payments in July 2025. At the press conference, sports media expert Galen Clavio noted the potential discontent among former players. “A lot of college athletes are going to be arguing that we are in the mid-2000s,” Clavio said, emphasizing that athletes who played before 2016 may question why they aren’t receiving compensation. This sentiment highlights the ongoing uncertainty around the proposal.

Further insight was given in an interview with the Thieneman brothers. Jake Thieneman had an overall positive perspective on the topic, citing the many opportunities NIL creates for players. Though he’s now a graduate, he wishes he’d had this opportunity when he played and believes past players should be compensated for their contributions to their programs. “I think it was unethical to prevent them from being compensated given the value they were providing to the schools and how much revenue they were generating,” he said.

Dillon Thieneman had a different perspective. While he acknowledged the positive effects of NIL, he also pointed out potential downsides. “Athletes are now able to get paid and receive other benefits from their play on the field and presence they have off the field,” he said. However, he added, “people do want to follow the money, and that leads to more people entering the transfer portal to find money for what they think they are worth.” Dillon Thieneman emphasized the growing divide between schools with established NIL programs and those with smaller budgets, resulting in a recruitment imbalance as top players gravitate toward wealthier schools. He also disagrees with the ruling that past players should receive compensation.

Dillon Thieneman shared his experience with securing an NIL deal, noting that the process can be somewhat stressful but rewarding. “The process can be a little stressful, but I enjoy it — getting to try new things like going to the INDY 500 track and recently doing a meal plan deal to receive frequent meals,” he said.

Jake Thieneman, who helped Dillon Thieneman negotiate his NIL deal, provided additional insight into the process. “For the deals between the player and the collective, the player or a representative for the player negotiates with the collective and comes to an agreement on how much they’ll be compensated annually based on the player’s position, their skill level, and their contribution to the team.”

The Thieneman brothers stand on different sides of the NIL discussion.

The debate over NIL continues to evolve daily. With college sports having a constantly growing media presence, this topic isn’t going away anytime soon. While the future remains uncertain, the opportunities for college athletes are only expanding.

Voxpop interviews with three strangers on their opinions of the House v. NCAA settlement