‘Your sister looks mean.’ That was the kind of remark Tebogo “Tebby” Kaisara heard from acquaintances nearly every time she went out with the woman who Tebby was told to call “her sister.” However, the woman was not a family member at all. Kaisara calls the woman her trafficker, and said she was a graduate student at Indiana University and an abuser who held Tebby against her will.

“I was just like,’ What happened?,” says Kaisara, as she recalls how it dawned on her she was no longer free.

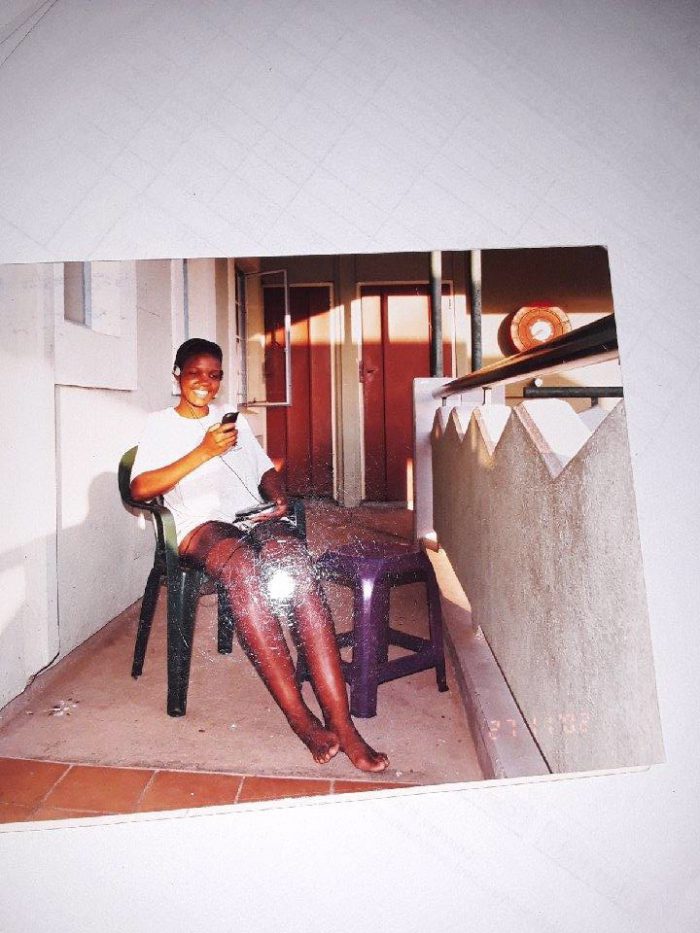

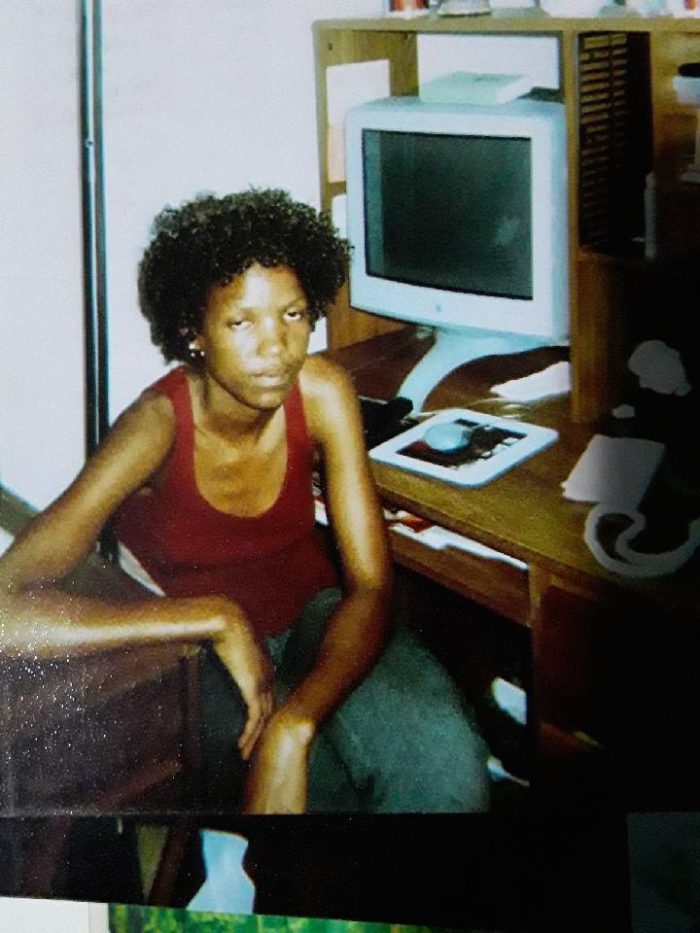

Kaisara came to America to escape another kind of abuse in her home in Botswana, South Africa. At the age of 10, she says she was raped–for the first time. Kaisara says she was sexually assaulted at age 15 by her own brother, who threatened to kill her if she ever told. Kaisara was one of eight children, and lived primarily with her aunt to alleviate her parent’s monetary struggles.

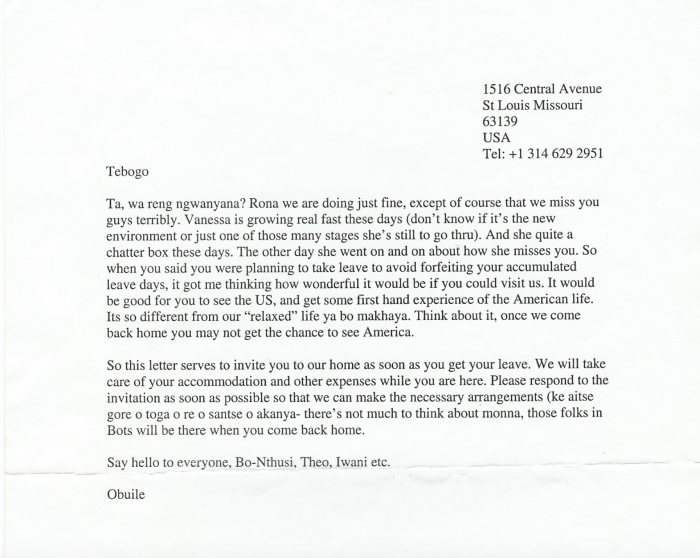

Kaisara says her cousin arranged for her to go to the United States for school. Her cousin said she would have a job lined up at a daycare in St. Louis and the opportunity to take college classes– all while living with a host family. At that point in her young life, anything seemed better than life in Botswana.

“I didn’t ask any questions, I got excited,” she says. But life was about to get much worse.

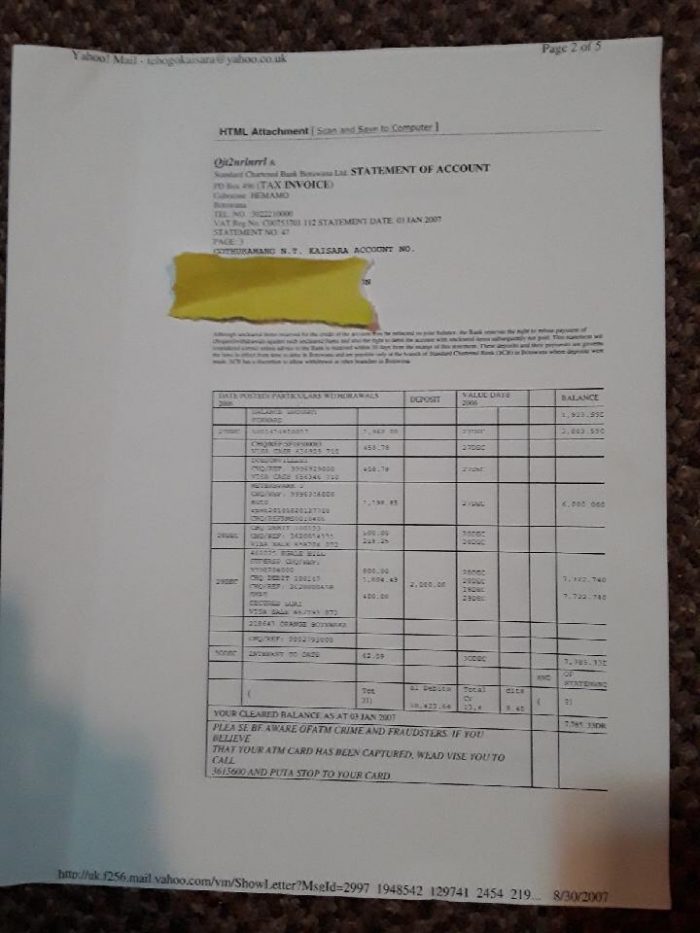

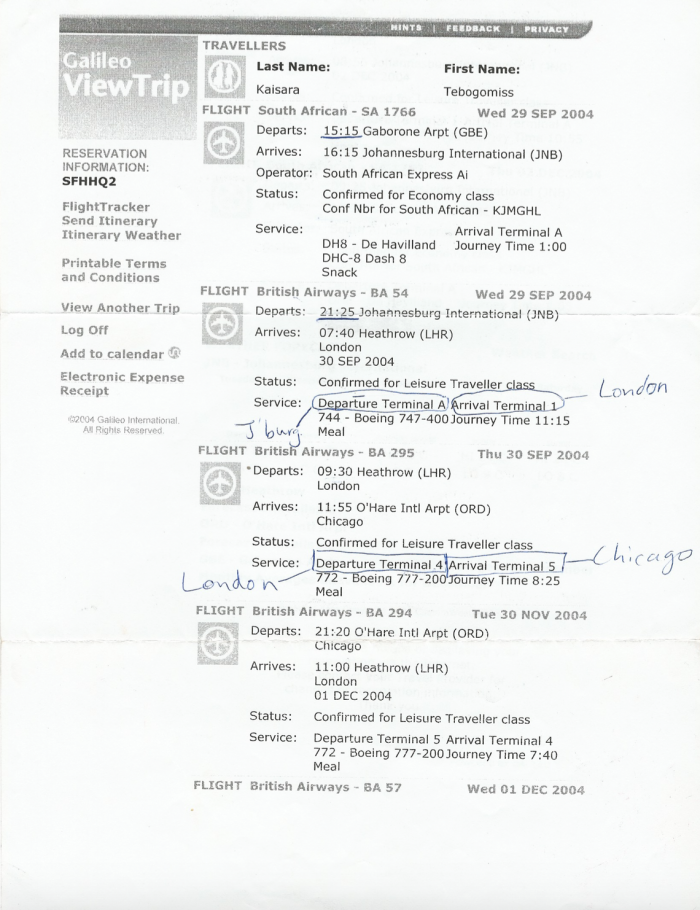

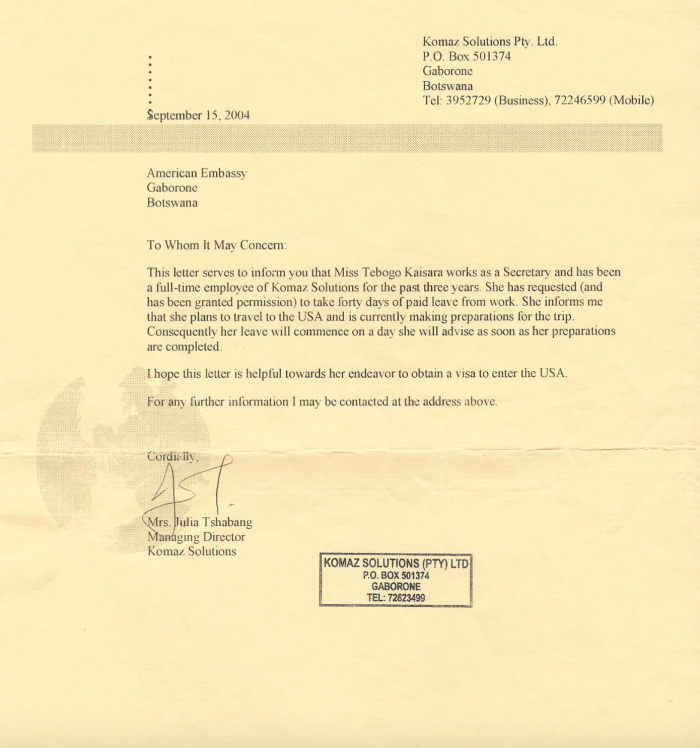

Her cousin, who Kaisara later realized was her trafficking recruiter, showed her VISA documents and letters from the so-called host family.

But on the plane, Kaisara noticed her destination was not St. Louis, but instead 300 miles away in Chicago, and then Indianapolis. The letters and documents were fake. Kaisara’s cousin was in on it all.

Confused, scared and alone, Kaisara remained hopeful that there was an explanation. When she arrived at the Indianapolis airport, she took a ride-share to the address her cousin gave her, on Lingelbach Lane in Bloomington, Indiana–the Bicknell Apartments located on IU’s campus.

Her ride-share driver seemed suspicious. When they arrived he walked her up to the house and asked if she was okay.

“He said, ‘I will show you how to call 9-1-1 in case of an emergency you call that. Even if you don’t talk, they will come where you are,” Kaisara recalls him saying.

The warning signs started.

Kaisara worked without pay as a caretaker for the woman and her two children. The woman, an IU School of Education Ph.D. student from Africa, confiscated Kaisara’s passport and documents, and told her not to call 9-1-1 or talk to police or Kaisara she would go to jail.

She says the woman forced her to refer to her as her sister in public.

“I just thought to myself, ‘Okay, what is this life that I am going to live now?” Hospital visits were out of the question, even when she says her trafficker pushed her down a flight of stairs, causing a deep cut to her leg. An Asian man saw her distress, helped her up, and even suggested she should see a doctor.

Her trafficker refused and gave her a used bandage to stop the bleeding.

Kaisara says later she fell gravely ill and needed surgery to remove a cyst from her head, but her captor refused a hospital visit again. Kaisara says that’s when she began contemplating suicide.

“I told her I wanted her to send me home if [she was] not able to take care of me,” says Kaisara. “This is ridiculous, just send me home.”

Kaisara says her captor told her the only way she would send her home, was dead. Kaisara threatened to call the police on her trafficker, telling her she had spoken to lawyers. It was then that her abuser panicked and kicked her out. Kaisara sat in the laundry room of the apartment complex, broke, with no place to go, contemplating ending her life.

“Im sitting there and I’m just crying, wondering what am I going to do. And all I can think of is commit suicide.”

But that moment of hitting bottom was the beginning of a new start. Kaisara says she began praying, and saw a vision of a wig-store she used to visit in town–picturing the woman who owned it.

“It was something that I’ve never experienced before,” she says. “I followed my directions from my ‘dream’ and walked for 30 minutes to go find this lady.”

Eventually, she found the wig-store and opened up about her plight to the woman there, Lisa Stieglitz, who gave her the keys to an apartment she was subletting. It was the first time she had told anyone.

Stieglitz also gave her a job. Kaisara braided hair to make money, and it wasn’t long before another friend contacted the FBI, prompting an investigation.

While there was not enough evidence to bring charges, Kaisara is now free. Kaisara says her trafficker left the country a few months after the case was reported.

“I used to live my life like I was in a shell, but I broke that shell,” she says.

Now, Kaisara takes classes at Ivy Tech and works four jobs. One is as a survivor advocate and expert for victims of human trafficking through the Indiana Trafficking Victims Assistance Program. She says it’s important to be aware of suspicious activity, and report it when you see it.

“I share my story because a lot of people don’t believe human trafficking exists,” she says. “Human trafficking happens everywhere and it can happen to any one.”